Blog and News > development > Becoming Static: Making the Move to Jekyll

Becoming Static: Making the Move to Jekyll

CANDDi’s public-facing corporate website recently made the switch from a dynamic, PyroCMS powered site to a static one generated by Jekyll. The process was surprisingly simple and hugely worthwhile.

The web developer community’s latest darling is Jekyll, a Ruby gem which makes generating entirely static websites easy. Despite it being primarily designed for blog focused websites, Jekyll has been used in multiple high profile projects; the most notable of which being Barack Obama’s campaign site. Now it’s powering this site, too.

CANDDi’s summer intern Dan Richardson lead this project to get canddi.com up to speed.

Jekyll is a Ruby gem which turns templates (written in Liquid) and content (written in Markdown) into a stand alone static HTML site. This is nothing new for those of us who built websites in the mid 90s, but quite a shift for the Wordpress generation.

##The advantages of static When you think of static websites, it’s possible that it brings back ‘fond’ memories of the early web. Before the mainstream CMSs such as WordPress became widely available, the majority of websites were simple static pages.

They were a pain to manage, often became unwieldy, and lead to a slew of dreadful desktop publishing programs to help manage them. They did however produce you a directory full of flat HTML files, and those has some significant advantages over a database driven CMS.

- Speed - With no dynamic content there’s no database to access, no templates to be rendered, and you can serve your pages blindingly fast.

- Security - No database and no interpreted language running means that vectors of attack are greatly reduced.

- Cost - You need less tin to run it. You might get away with not having a server at all.

- Content as code - tech companies are really good at managing code, less so content.

Speed

The lack of CMS and database technologies has the effect of cutting out the middleman between the visitor and their requested content other than the webserver. If you combine this with a global caching system such as Amazon’s CloudFront or Fastly and you can get some blazingly fast response times.

Security

What doesn’t exist cannot be attacked. With no database and no more PHP we’ve removed several compromisable systems. We’ve also removed the problems that come from using the same code base as lots of other users too, namely automated attacks. WordPress sites are now infamous for being the targets of brute force botnet attacks.

Cost

The cost might seem trivial at first, because hosting a site is not that expensive, but hosting flat files is even cheaper. A tiny server will happily serve up thousands of static pages a second. In fact, the end goal for CANDDi’s corporate site is for it to be hosted in a simple Amazon AWS bucket, literally reducing its monthly upkeep to pennies. One of the coolest things about Jekyll is that because the resulting site is so simple, it can actually be hosted entirely for free through GitHub Pages (as long as you don’t require the additional functionality that Jekyll’s plugin system provides).

There is an increased cost of content production to begin with (the lack of WYSIWYG editor might be a problem), but as CANDDi is a company of coders, we’re fine with a bit of Markdown and Git.

Content as code

If your content is written in text files you can bring all the tools you use to manage code to your content. In our case that means Git for version management, GitHub+fork+PR for changes and GitFlow. We can edit content in Sublime, version it sensibly, review and edit faster than when we had to remember usernames and passwords for an infrequently used GUI.

It also means that the delta between development and production is tiny. Anybody who’s tried to version control a live CMS site (do you check the theme in separately? What about the database? How do we roll this out without removing the pages that were added since we cut a DB copy?) will know why this was so exciting.

##CMSs exist for a reason Please don’t read this as an article kicking Wordpress, PyroCMS and friends in the teeth. The main advantages of using a content management system are still evident and for many users Jekyll wouldn’t be appropriate, however for us at this time, Jekyll is a great move.

If you or your client isn’t going to cope with manually creating page entries, compiling the code and rsyncing it up to the right location, a CMS is the way to go. We had a lot of milage from PyroCMS and benefitted greatly from the community formed around it.

##Making the move

After making the decision to move, we had a functional (yet incomplete) version actually of canddi.com up and running in a couple of days. Jekyll creates pages through the use of templates (called layouts), which can be split into individual modules (called includes). This allows for the flexibility of being able to alter all of a site’s pages in one go, while remaining static. Because we wanted the new site to look as close as possible to the PyroCMS version, it was simply a case of copying the existing site’s HTML code into appropriate templates.

The main challenge with regards to site structure came from replicating Pyro’s functions concerning content; displaying given pages (complete with dropdown children) in the navigation bar or listing months in which blog posts were made, for example, took some consideration. For more interesting functionality such as this Jekyll utilises Liquid Markup, which developers of Shopify sites will be familiar with. Jekyll allows for global variables to be defined in the site’s configuration file which, in combination with specific page/post properties, can result in very flexible amounts of functionality.

Transferring existing blog posts from the CMS to Jekyll proved to be the most time consuming process of the project. Jekyll generates blog posts through a combination of the markup language Markdown and a YAML front matter section, which details the post’s metadata such as date and title. While users making the move from WordPress will be glad to hear that Jekyll actually comes pre-baked with functionality to import existing WordPress posts from a database and convert it into this format, unfortunately Pyro users (at the time of writing) don’t have this luxury. A custom parser had to be constructed to strip the metadata and content from Pyro’s XML export and transfer it into the YAML and content sections. These files were then passed through the exceedingly helpful html2markdown.com in order to strip the junk HTML that Pyro’s WYSIWYG text editor had generated before handing them over to Jekyll.

Jekyll’s use of Markdown makes it extremely simple to create new posts, thanks to how easy it is to interpret its syntax. With this in mind, it seemed a shame to pollute these clean looking files with messy HTML tags when we required functionality which Markdown couldn’t provide. For example, we wanted to have the ability to make images float to one side and embed YouTube video into posts. To achieve this functionality without having to use HTML within the blog post files we created several plugins which defined Liquid markup tags. This proved quite successful, making future posts far easier to create and edit.

For example, this:

<iframe width="560" height="315" src="//www.youtube.com/embed/yV9rzYo4Jrk"

frameborder="0" allowfullscreen></iframe>

Became this:

{% YouTube yV9rzYo4Jrk %}

The gotchas

Like any shift of technology, we got caught out by a few things. They were all very simple to solve in the end, but worth knowing.

Your URLs are now “raw”

Every URL that came through Pyro was interpreted, meaning the case sensitivity and whether or not there was a / on the end didn’t matter. Now every URL either hits a file, or doesn’t. BaDlY cased URLs will now fail, so use a tool like Screaming Frog to map your current site, and check your logs for oddities coming in.

These are not the status pages you are looking for

As mentioned above, Pyro handles all of our error pages, so we now needed some. This is a simple matter of sorting out the content for the page and a few likes or Apache config to configure them. Trivial, once we knew we needed to do it.

Case Sensitivity strikes back!

All of our development is done on Macs. Macs aren’t as case sensitivity about file names as a Linux server. After going live we had to make a couple of quick amendments to correct problems which weren’t seen locally.

Wait, we can’t do that anymore…

The unfortunate thing about removing your database is that, well, you don’t have a database. Previously Pyro had been able to handle elements such as form submissions and blog comments. Unfortunately Jekyll just can’t do that, so we had to rely on third-party services. Our comments are now handled for free by Disqus and we use Salesforce’s Web-to-Lead system to handle form submissions. We’re also running a little thing called CANDDi, which certainly helps.

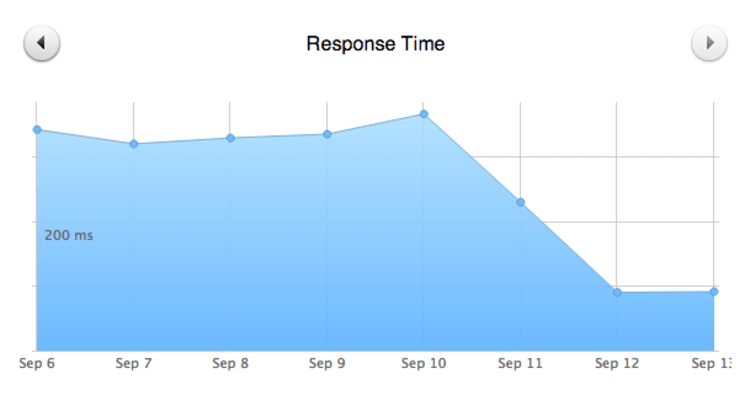

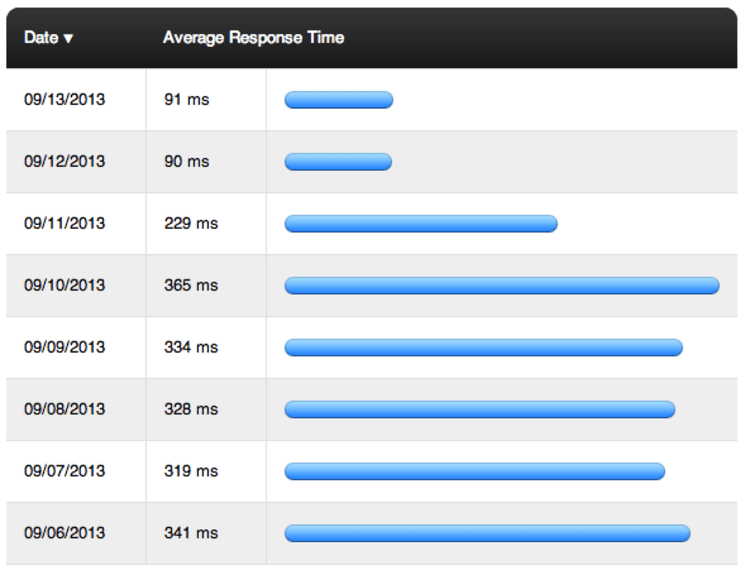

##The result Hopefully you’ll agree that the site’s transfer was a success. Even if you’re a regular visitor to the site, it’s likely that you wouldn’t have noticed any differences other than it being a bit snappier. Much snappier, in fact:

The graphs above show data collected using Pingdom and clearly illustrate the difference that going static made. In fact, the response time for the site was quartered - and that’s without using any geo location caching or content delivery networks. Our next step for the site is to host it from an Amazon S3 bucket and watch the site’s hosting costs fall through the floor.

Not only is the new Jekyll site far faster, but it’s also much more secure and will be able to run for a month for less than a bottle of cola. If you haven’t considered Jekyll for any of your future projects, it might be worth a look - certainly don’t simply disregard it as simply being a blogging tool.

Next week’s blog topic will be about how we use git in our workflow to manage and review our content changes. Be sure to check back then.

We’re currently hiring get in touch if this sort of thing (along with AWS, Mongodb, Redis, Node and PHP) sounds exciting.